NEW YORK STATE MEDICAID REDESIGN TEAM (MRT) WAIVER

- Draft DSRIP Waiver Amendment Proposal is also available in Portable Document Format (PDF)

1115 Research and Demonstration Waiver #11–W–00114/2

Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) Amendment Request

New York State Department of Health Office of Health Insurance Programs

One Commerce PlazaAlbany, NY 12207

September 17, 2019

Section 1. Historical Narrative Summary of the Demonstration

Introduction

New York seeks a four (4) year waiver amendment to further support the cost savings and quality improvements being driven through the Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) Promising Practices. As with the original Medicaid Redesign Team (MRT) waiver, New York State seeks a continuation of DSRIP for the 1–year balance of the 1115 waiver ending on March 31, 2021 and conceptual agreement to an additional 3 years from April 2021 to March 31, 2024. Thus, the full four–year extension/renewal period (1–year extension and 3 years of renewal) would span from April 1, 2020 through March 31, 2024. New York is requesting $8 billion over this period to be invested toward DSRIP Performance, Workforce Development, Social Determinants of Health, and an Interim Access Assurance Fund.

Background

On April 14, 2014, the State of New York (the State) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reached agreement on a groundbreaking waiver that allows the State to invest $8 billion of the $17.1 billion in federal savings generated by the Medicaid Redesign Team (MRT) reforms for comprehensive Medicaid delivery and payment reform primarily through a Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) program. The $6.42 billion DSRIP program provides incentives for Medicaid providers to create and sustain an integrated, high– performing health care delivery system that can effectively and efficiently meet the needs of Medicaid beneficiaries and low–income uninsured individuals in their local communities by improving the quality of care, improving the health of populations and reducing costs.

The DSRIP program promotes community–level collaboration and aims to reduce avoidable hospital use by 25 percent over the five–year demonstration period, while financially stabilizing the State´s safety net providers. A total of 25 Performing Provider Systems (PPS) were established statewide to implement innovative projects across three domains: system transformation, clinical improvement and population health improvement (New York´s Prevention Agenda). All DSRIP funds are based on achievement of performance goals and project milestones.

DSRIP Demonstration Progress to Date

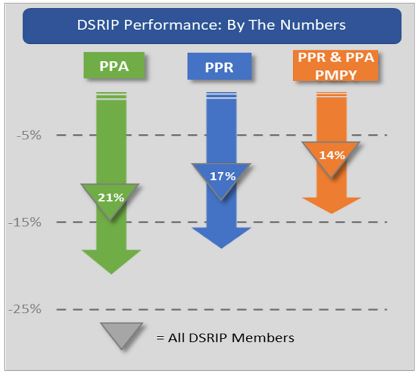

Through the innovative efforts of the 25 PPS and their partners, New York has achieved significant reductions in avoidable hospital use through Measurement Year 4 ending June 2018. Potentially Preventable Admissions (PPAs) have been reduced by 21%, and Potentially Preventable Readmissions (PPRs) by 17%. The combined reductions are estimated to have reduced per member per year costs by approximately 14% for the last four measurement years or savings of more than $500 million for these events alone.

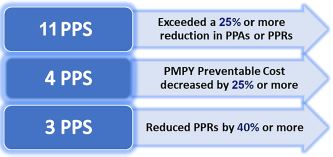

But those are just the averages. An even more impressive story emerges when looking specifically at those PPS adopting the most promising practices. Eleven PPS saw avoidable admission and readmission reductions of over 25 percent, with a few PPS driving decreases of over 40 percent from baseline. Also, when looking from a patient lens, those members qualifying for health home care management saw average reductions of 25 percent or more in both measures of avoidable hospital use.

Standout Performance: Exemplary PPS

In addition to these reductions in avoidable hospital use, the DSRIP Independent Evaluation has shown even more overall objective success including improved performance in the majority of behavioral health and population health measures in the interim evaluation period (through DSRIP year 3). Additionally, results for the asthma medication ratio measure improved, as did early indicators of system change, such as members connectedness to providers (usual source of care) and reduction in uninsured use of emergency department (self-pay ED visits). Of note, PPS that performed well on avoidable hospital use also tended do very well on other high–priority DSRIP measures associated with behavioral health and other chronic illness management and improvement.

As a result of the DSRIP work thus far, integrated delivery networks have developed, strengthened and matured over the DSRIP period to collectively improve performance in both quality and cost–savings. These new networks have advanced never–before–tested service models and now have had the shared experience of meaningful collaboration to exceed performance targets and earn the most challenging of DSRIP incentive payments. By doing so, these networks have been able to further partner and participate in innovative pilot value–based payment (VBP) arrangements. In just a few short years, New York has significantly moved NY Medicaid from fee for service to paying for value. Today, over sixty percent of NY Medicaid managed care dollars are contracted under a VBP model. New York was first in the nation to require that risk–based arrangements include social determinants of health (SDH) interventions and contracting with one or more community–based organizations (CBO). Forty percent of the VBP risk arrangements have a defined SDH intervention with inclusion of community level human and social services organizations.

The very promising population health work and early forays into VBP are demonstrating, however, that more time is needed to directly support the best DSRIP work and facilitate VBP maturation to continue the invaluable progress made to date. This additional time will allow DSRIP to build on extremely promising outcomes–based performance while more fully benefiting from collective shared savings and upstream reinvestment opportunities resulting from those efforts. Specifically, current VBP arrangements built exclusively around primary care provider (PCP) attribution and networks do not completely embrace the kind of comprehensive integrated primary care, behavioral health, and other social care capacities that have been at the heart of most of the DSRIP success. Thus, the required shared savings to power the most promising DSRIP practices will be available on a broad scale when VBP contracts mature to add more partners and embrace more sophisticated payment models that share accountability, performance, and payment risk across a broader continuum of providers collaborating on outcome improvement with pre–arranged shared savings models.

Some of the best examples of value–oriented collaborative work have been driven by DSRIP Year 3 and Year 4 incentives when project implementation matured to meet the needs of pay– for–performance (P4P) based accountability. Transformative work has been a significant undertaking of building partnerships and trust and clearly requires more time for maturation at scale. The continuum of community health and social service providers that has greatly contributed to moving the needle on population health must be recognized in VBP arrangements. Managed Care (MCO) engagement and partnership now need to be more meaningfully integrated to construct VBP agreements that recognize and sustain the new, non–traditional community partnerships that have demonstrated the significant gains in performance and cost–savings referenced earlier.

Section II. Changes Requested to the Demonstration

Continuing the Transformation

New York seeks a four (4) year waiver renewal to further support the cost savings and quality improvements by aligning with federal goals and through the DSRIP Promising Practices cited in the introductory section and further described below. New York is requesting $8 billion over this period to be invested as follows: $5 billion DSRIP performance; $1billion Workforce Development; $1.5 billion Social Determinants of Health and $500 million Interim Access Assurance Fund. As with the original MRT waiver, NYS seeks continuation of DSRIP for the 1– year balance of the 1115 waiver ending on March 31, 2021 and conceptual agreement to an additional 3 years from April 2021 to March 31, 2024. Thus, the full four–year extension/renewal period (1–year extension and 3 years of renewal) would span from April 1, 2020 through March 31, 2024.

Aligning with Federal Goals

Healthcare Transformation is most effective when the State and Federal partnership align goals. The State has and will continue to assess all elements of the amendment request for alignment with federal performance measurement approaches, programmatic approaches, promising practices from The Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) and the Quality Payment Program, and efforts by the Medicaid Innovation Accelerator Program.

In the next phase of DSRIP, the State will focus on higher–value practices that are clearly aligned with federal priorities. As outlined in Table 1 of Appendix A, these federal priority areas include: SUD Care and the Opioid Crisis; Serious Mental Illness (SMI)/Serious Emotional Disturbance (SED); Social Determinants of Health; Primary Care Improvement and Alternative Payment Models. Within those priority areas the following promising practice categories are proposed for continuation:

- Expansion of Medication–Assisted Treatment into Primary Care and ED settings;

- Partnerships with the justice system and other cross–sector collaborations;

- Primary care and behavioral health integration;

- Care coordination, care management, and care transitions;

- Expansion of Mobile Crisis Teams (MCT) and crisis respite services;

- Focus on patients transitioning from IMDs to the community;

- Focus on Seriously Mentally Ill/Seriously Emotionally Disturbed populations;

- Addressing Social Determinants of Health through Community Partnerships; and

- Transforming Primary Care and Supporting Alternative Payment Models.

The DSRIP Promising Practices

The DSRIP Promising Practices are described in a report issued by the United Hospital Fund1 in July 2019 entitled DSRIP Promising Practices: Strategies for Meaningful Change for New York Medicaid. (See examples in Appendix B). These initiatives demonstrate the transformative regional and community collaborations among a diverse set of health system and social service providers that have impacted quality and clinical outcomes and earned PPS the performance– based DSRIP incentive payments. These unprecedented efforts have been labor–intensive, requiring the formation of new relationships to better serve consumers and iterative testing as to which innovations yield the best results at the local level. We have learned new workflows take time for maturation to yield optimal results.

During the initial DSRIP period, each region has learned much about the most effective partnerships to advance this important work. In some cases, the PPS as an entity has been the major driver of change. In others, subgroups working in carefully tailored medical markets have collaborated to address specific issues or subpopulations. During the next phase of DSRIP, additional flexibility will be allowed to fund focused provider/CBO/MCO teams to implement the high–priority DSRIP promising practices.

The proposed amendment will allow the State to further analyze the practices´ performance results for appropriate allocation within a VBP arrangement. Additionally, the amendment will support the innovative transformative elements realized under DSRIP to be further developed and scaled with the MCOs as part of VBP arrangements, while driving more careful alignment with current federal healthcare initiatives.

The Second Generation – Value–Driving Entities

Early stakeholder feedback on a waiver extension/renewal included several requests for additional flexibility in the operational structure of the next DSRIP funded entity. Consistent with this request, during the proposed DSRIP extension period, additional flexibility will be implemented in the DSRIP structure to align funding to the best future management structure for a given region/market.

The Second Generation "Value–Driving Entities" (VDE) will consist of PPS (or a subset of PPS), provider, CBO and MCO teams specifically approved by the state to implement the high–priority DSRIP promising practices. With 4.7 million people enrolled in Medicaid managed care, the inclusion of the MCOs as active partners in the delivery system collaboration and in the development of more sophisticated VBP models is necessary to best support the maturing networks.

The Qualified Entities (or QEs – the state´s regional health information organizations that connect to the statewide Health Information Network) would also be integrated into the collaborative partnerships to be strategic partners in sustaining and enhancing the partners´ bidirectional data exchange capabilities.

Value–Driving Entities will continue to be assigned specific regions/markets and attributed populations but will have the flexibility to either modify the existing PPS structure to accommodate additional representation from the different sectors (CBO, MCO) or instead propose new teams from a subset of provider/CBO/MCO/QE groups.

All Value–Driving Entities will be required to bring MCOs in the region into the management and operational structure to replicate and scale (and make ready for VBP contracting) the promising practices. Ideally, Value–Driving Entity governance would include additional representation from community–based providers, including primary care, behavioral health and long–term care to review the types of efforts and investments necessary to improve regional performance. The single overarching goal of the VDE will be to drive the DSRIP promising practices and the additional high–need projects referenced below to the point where they are fully supported by VBP contracts by the close of the third year of the DSRIP extension.

Value–Driving Entities will be selected based on the history of performance improvement, strength of provider, MCO and community–based organization partnerships, an inclusive governance structure that includes a range of providers, MCOs and CBOs in executive steerage, and importantly, the potential to sustain the selected DSRIP promising practices under VBP arrangements by the third year of the extended demonstration.

The infrastructure of primary, pre–acute, post–acute, in–home, behavioral health, and long–term care collaborations formed in the DSRIP program will serve as the foundation and will be expanded and more fully leveraged by the VDE. PPS should be well positioned to lead VDE by leveraging plan, provider and community partnerships.

Value–Driving Entities will build upon existing value–based payment networks including Integrated Delivery Systems, ACOs, IPAs, and NYS Behavioral Health Care Collaboratives (BHCCs) and other configurations specifically designed to advance DSRIP promising practices and mature them through value–based payment contracting.

Section III. Additional High–Need Priority Areas

CMS and the State agreed to a DSRIP demonstration focused on reducing avoidable hospitalizations by 25 percent. New York is well on its way to meeting this goal with a reduction of 21% shown for measurement year 4. However, certain high–need and high–cost populations such as higher–risk children and members needing long–term care did not benefit directly from most DSRIP initiatives unless a Medicaid–measured avoidable hospitalization could be impacted such as ER visits for childhood asthma.

The DSRIP promising practices have now demonstrated a variety of opportunities to expand initiatives to improve care and reduce costs of additional populations. The unique needs of Value–Driving Entities´ attributed members and their individual community contexts will require providers, MCOs and CBOs to focus the promising practices to address their specific population challenges to tackle their most pressing community health needs. These initiatives would address domains of health system transformation, clinical improvement, and elements of the New York State Prevention Agenda. This focus on promising practices will lay the groundwork for further adoption of VBP that is specifically designed to meet the needs of potentially high– cost, high–need subpopulations. Below are two illustrations of these areas.

Reducing Maternal Mortality

As compared to 2010, New York has made improvements in reducing maternal mortality rates, yet New York still ranks 30th in the nation among states. In April 2018, Governor Andrew M. Cuomo announced a comprehensive initiative to target maternal mortality and reduce racial disparities in health outcomes. The multi–pronged initiative included efforts to review and better address maternal death and morbidity with a focus on racial disparities, expanding community outreach and taking new actions to increase access to prenatal and perinatal care. In August 2019, Governor Cuomo signed legislation to create a Maternal Mortality Review Board charged with reviewing the cause of each maternal death in New York State and making recommendations to the Department of Health on strategies for preventing future deaths and improving overall health outcomes.

With NY Medicaid covering 50 percent of the births in the State, Medicaid must be part of the solution. Under the DSRIP amendment, a community with high maternal mortality and low birthweight deliveries could leverage existing public health projects to develop a project leading to adoption of a maternity bundle that integrates promising practices from beyond DSRIP (e.g. Centering Pregnancy).

Children´s Population Health

Approximately 47% of the state´s children are covered by Medicaid. The next implementation phase would extend successful practices to children in the areas of chronic care management, behavioral health integration, pediatric–focused patient–centered medical homes, and attention to adverse childhood experiences and social determinants. Care transitions and care management for targeted groups have been very successful and would be expanded to serve this population, in collaboration with the Health Homes Serving Children . Further integration of community health workers into provider teams to assist with chronic care management for asthma has also been very successful. Expanding behavioral health urgent care centers for children has decreased emergency admissions and provided further access to care.

For children with SED, transitional care teams of clinicians and peers bridging psychiatric inpatient to community settings would be deployed. Use of telemedicine for care management of residential populations for ED triage and expansion of crisis stabilization programs would improve management of overall care and minimize avoidable admissions.

Children with special health care needs, HIV/AIDS, and end–of–life/palliative care populations are other examples of special populations where collaborative improvement projects could open the door to more robust VBP approaches.

Long–Term Care Reform

Between 2015 and 2040, the number of adults age 65 and over in New York State is projected to increase by 50 percent, and the number of adults over 85 will double. New York will need to focus on the demographic shift and to address the continuum of care services and system reform efforts for sustainability. The long–term and post–acute care (LTPAC) and other service programs form an important continuum to allow people to age in place safely with quality of life while minimizing costly institutional stays and acute care episodes. DSRIP transformation efforts

to reduce avoidable acute care admissions impacted all populations and included strengthening transitions between hospital to SNF and hospital to home. Promising work was implemented to solidify hospital and SNF collaborations through the INTERACT projects on quality and clinical care protocols. PPS assisted SNF partners in electronic health record implementation and connectivity with the Qualified Entities for clinical data exchange. While Medicare and Medicaid data integration is clearly a challenge, during the renewal timeframe matched Medicare and Medicaid claims data will be available and integrated to assist providers on measuring DSRIP and VBP performance as well. Further exploration of bundling and value–based payment options for this sector will be married to continued exploration of new Managed care delivery models to further strengthen and integrate the broader continuum of care for patients needing longer–term services and supports.

Workforce investments for the LTPAC and services for older adults are also critical. While the number of adults age 65 and over is growing rapidly, the number of working–age New Yorkers able to serve them is declining. By 2040, the number of adults between 18 and 64 for every adult over age 85 will drop from 28 to 14. There is a current LTPAC workforce crisis throughout much of the State, and that crisis is projected to deepen over the next twenty years. Additional programs that DSRIP fueled through the PPS workforce collaborations should continue to identify the system reforms needed to support the aging population and the workforce needs that will be required. These would include subsidies and stipends for participating in aide certification and nursing programs; loan forgiveness programs for nursing graduates; and subsidies for work barrier removal including child care for LPNs and aides. Needs are particularly acute in rural areas and will require innovative approaches.

Collaborations of Value–Driving Entities, MCOs, and CBOs would target a specific high–need population for activities meeting a limited set of state–defined criteria designed to move towards VBP and would initially use available data (including QE data) to define the population and the opportunity(ies) for improvement. This would include an analysis of the clinical and claims data, which would also identify measures (from the existing VBP measure sets where possible) for which the collaborators would be willing to hold themselves accountable for improvement.

These measures would then be integrated into the performance measure set for the Value– Driving Entities, weighted by the size of the defined high–need population in comparison to the whole of the attributed population.

Section IV. Continued Investments/Improvements

Continued Workforce Flexibility and Investment

Many of the DSRIP initiatives that have proven results rely on non–traditional, non–clinical workforce to achieve project goals by helping members better navigate the clinical and social service systems to best meet their unique needs. The Value–Driving Entities will require ongoing flexibility to use earned dollars to support non–clinical workforce (e.g. community health workers, peers, patient/community navigators, etc.) as they work with the MCOs and CBOs to design VBP approaches that support these value–adding team members for the long–term. Required workforce–related planning and reporting in the extension period would focus on the data that all partners, including community–based partners, would need to assess intervention costs and savings for purposes of future VBP. A portion of the VBP bonus payment could be based on integration of non–traditional workforce into higher–level VBP arrangements.

Regional PPS and partner collaboratives focused on local gaps in the delivery system and implemented workforce strategies such as community college community health worker (CHW) training courses, training stipends, scholarships, and recruitment/retention of needed clinical and non–clinical staff. The local collaborations were nimble in mobilizing available community institutions for workforce training, recruitment, and placement in relatively short timeframes to impact performance at provider program sites. The Value–Driving Entities should be able to continue to assess and invest in local workforce needs to fuel innovative approaches to achieve improvement in outcomes.

Coordinated Population Health Improvement – A multi–player context for reform

Leveraging previous population health and chronic disease clinical improvement projects, Value–Driving Entities would be required to integrate Prevention Agenda goals across their Program Extension Area projects. This integration should focus on extending promising practices upstream towards primary and secondary prevention, to increase potential for bending the longer–term utilization and cost trends. Further, Value–Driving Entities, while focused on Medicaid and Medicare for the duals from a performance perspective, should consider a multi– payer lens when implementing the promising practices to promote 360–degree population health and to further the sustainability of these reform approaches.

New York has led the nation in requiring the use of SDH interventions by investing state Medicaid dollars in housing, by promoting SDH and community–based organizations inclusion through DSRIP and requiring managed care plans to contract for SDH interventions in risk– sharing VBP contracts. Strong partnerships of CBOs and PPS have been formed under DSRIP for innovative approaches to integrate SDH services as part of treating the whole person in impacting the non–medical factors in order to improving their outcomes.

As part of the next implementation phase, the state proposes to further advance this work through "Social Determinant of Health Networks" (SDHN) to deliver socially focused interventions linked to VBP. Lead entities will be selected through a competitive procurement with Value–Driving Entities/PPS being eligible applicants. The lead entity of the SDHN will create a network of CBOs that will collectively use evidence–based interventions to coordinate and address housing, nutrition, transportation, interpersonal safety and toxic stress.

The state would designate regions and pick a lead applicant in each region to 1) formally organize CBOs to perform SDH interventions; 2) coordinate a regional referral network with multiple CBOs and health systems; 3) create a single point of contracting for VBP SDH arrangements; and 4) assess Medicaid Members for the key State–selected SDH issues and make appropriate referrals based on need.

The SDHNs will target Medicaid members with complex health and social needs, and children/families with children experiencing, or at risk of, significant and multiple adverse childhood experiences. Contracts and funds would flow through the plans to the SDH network to align SDH interventions with value–based services contracts.

Addressing the Opioid Epidemic

Significant gains have been made to advance care for those with a diagnosis of Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) specifically and Substance Use Disorder (SUD) generally. From DSRIP Measurement Year 0 to Measurement Year 4, potentially preventable ED visits (PPVs) for persons with a behavioral health diagnosis (includes SUD and mental health conditions) have decreased by nearly 2%, despite over a 35% increase in eligible members over the same period. The next phase will build on the best practices implemented in the current demonstration such as broad screening for OUD/SUD in primary care practices (e.g. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment, (SBIRT)), Medication–Assisted Treatment initiated in emergency departments and primary care practices and further focused on the justice–involved population, hospital to community linkages, and deployment of peers in care transitions, navigation, and recovery). Value–Driving Entities will partner with their regional Centers for Treatment Innovations (COTIs), NY State´s Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services treatment providers that are focused on engaging people in their communities by offering mobile clinical services, as well linking people to other appropriate levels of care. COTIs target un/underserved areas and expand access to tele–practice, substance use treatment services, and linkage to Medication–Assisted Treatment, as well as peer outreach and engagement within the local community.

Section V. Performance Measurement

Measures and Performance Payments to Facilitate Future Value–Based Payment Models

During the DSRIP period, substantial work has been done to begin aligning quality measures across initiatives and strategically narrow measure sets to those measures that have the most likelihood of driving future value for Medicaid (e.g. MIPS, CMS core sets, NYS Quality Assurance Reporting Requirements for MCOs, NYS PCMH measures, VBP Roadmap–defined arrangements with their associated measures). The amendment request will build on alignment work to date by suggesting close collaboration with CMS on initial measure specifications that:

- Appropriately measure performance on the DSRIP promising practices;

- Align with the CMS Meaningful Measures Framework, CMS core measure sets, and other federal and state measures already in use;

- Focus on areas with existing poor performance and/or broad performance disparities;

- Are clinically relevant, reliable, valid, and feasible for use both as performance measures for purposes of the amendment request and as VBP measures at the provider level; and

- Are sufficiently streamlined to allow for both universal application for Value–Driving Entity performance payment and widescale adoption of all or most of the measures in VBP arrangements

The agreed–upon measures will be used for performance payment under the amendment and will be reviewed by the existing VBP Clinical Advisory Groups as they annually reconsider VBP measures. Performance payment under the amendment would continue to focus on payment for quality improvement but could instead be based on improvement across the entirety of the measure set, not just on measures attached to individual projects. A bonus payment program would be included to reward ongoing high performance and to reward Value–Driving Entities that enter into higher–level (i.e. more risk) VBP contracts with MCOs specifically using the aligned amendment and VBP measures. The VBP portion of the bonus payment could include additional elements of overall utilization decreases and/or resulting cost savings.

Additional process measures will be considered for reporting purposes only, especially to track MCO, CBO, and QE engagement. The state will also continue to provide PPS/Value–Driving Entities with relevant claims–based measures for their attributed populations beyond the aligned and streamlined amendment performance payment measure set.

As Value–Driving Entity performance begins to facilitate the partnerships and structures necessary to develop APMs with MCOs and CBOs, the State will support these efforts through continued state and regional population health analytics and via integration of existing primary care practice transformation incentives in those emerging APMs. This would leverage much of the PPS and State infrastructure developed during the DSRIP period and eventually create opportunities for the State to incentivize partnerships that developed advanced payment models that meet to–be–defined criteria for best–practice adoption in areas such as additional system transformation, data usage and sharing, continuous performance improvement, network and service rationalization, and regional population health improvement. As the Gen 2 partnerships progress, the promising value–based payment models will be tracked and reflected in New York´s VBP Roadmap.

Section VI. Interim Access Assurance Fund 2.0

Previous amendments to the 1115 demonstration provided for an Interim Access Assurance Fund (IAAF) to ensure that sufficient numbers and types of providers were available in the community to participate in the transformation activities contemplated by the DSRIP Program. The IAAF authorized payments to providers to protect against degradation of current access to key health care services.

IAAF 2.0 is a critical component of health care reform in New York. DSRIP success in driving down avoidable hospitalizations including readmissions and avoidable ED visits have curtailed revenue for some of the state´s hospitals serving the most vulnerable Medicaid and uninsured patients. This comes at a time when the necessary risk and value–based payment structures are not mature enough to have provided a path for shared savings to at least partially supplant this revenue loss. Many facilities are focusing new resource development on urgent care, ambulatory, and other forms of non–institutional care, but revenue loss on the inpatient side without additional transition funding could serve to permanently destabilize some critical access and essential safety net providers. In the proposed waiver period for IAAF 2.0, $500M will be made available to provide supplemental payments that exceed upper payment limits, DSH limitations, or state plan payments, to ensure that current trusted and viable Medicaid safety net providers, according to criteria established by the state consistent with agreed–upon STCs, can fully participate in the DSRIP transformation without unproductive disruption. The IAAF is authorized as a separate funding structure from the DSRIP program to support the ultimate achievement of DSRIP goals.

IAAF 1.0 supported 34 financially distressed rural and urban critical access and safety net providers during 2014–2015, the initial year of the DSRIP program. In addition to participation in the DSRP program, the State also required that recipients of IAAF develop and implement strategic transformation plans to improve their financial sustainability. Transformation projects included initiatives such as rightsizing inpatient capacity, expanding ambulatory care, and integrating into larger community or regional health care systems. However, the multi–year nature of these transformation plans, the compounding revenue loss impacts of DSRIP initiatives that reduced inpatient and emergency department utilization, and overall market forces generated assistance needs (in both amount and duration) well in excess of authorized IAAF funding. In response, New York State established additional assistance programs beyond IAAF to provide transitional operating support and capital support for strategic initiatives.

A number of the original IAAF recipients have "graduated" from these assistance programs by improving their operating margins, increasing quality, meeting DSRIP goals, and restructuring to better meet the essential health care needs of the communities they serve. However, since the original IAAF 1.0 funds were allocated, additional hospitals that provide essential community health services have become financially distressed, and some of the original IAAF hospitals continue to have significant challenges, particularly in communities that are geographically isolated or economically depressed. IAAF 2.0 funding will supplement the ongoing State assistance programs for financially distressed hospitals and help accelerate transformation of acute and ambulatory health care services in these communities.

IAAF 2.0 payments will again be structured to ensure that sufficient numbers and types of providers are available to Medicaid beneficiaries in the geographic area to provide access to care for Medicaid and uninsured individuals while the state continues its transformation path. The IAAF payments shall be limited to providers that serve significant numbers of Medicaid individuals and that the State determines have financial hardship in the form of financial losses or low margins. In determining the qualifications of a safety net provider for this program and the level of funding to be made available, the State will take into consideration both the number of Medicaid beneficiaries being served and whether the funding is necessary (based on current financial and other information on community need and services) to provide access to Medicaid and uninsured individuals. The State will also seek to ensure that IAAF payments supplement but do not replace other funding sources.

Section VII. Evaluation

Per the STCs, DSRIP has contracted with an Independent Evaluator (IE), the State University of Albany. The IE submitted the Interim Evaluation Report on August 2nd, 2019 and the final Summative Report is due June 30, 2021. Evaluation parameters and approach for the current DSRIP waiver amendment will be reviewed with CMS with the waiver amendment approval to determine how best to approach an evaluation of the second phase of DSRIP.

Section VIII. Budget Neutrality Compliance

New York is requesting $8 billion in federal financial participation through this waiver extension for the following purposes as described in detail in this document:

DSRIP Programmatic Breakdown ($ millions)

| Funded Program | State Share | Federal Share | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| DSRIP Performance | $5,000 | $5,000 | $10,000 |

| Workforce Development | $1,000 | $1,000 | $2,000 |

| Social Determinants of Health | $1,500 | $1,500 | $3,000 |

| Interim Access Assurance Fund | $500 | $500 | $1,000 |

| Total | $8,000 | $8,000 | $16,000 |

DSRIP Programmatic Breakout by Waiver Year (Federal $ millions)

| Funded Program (Federal $) | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSRIP Performance | $2,750 | $1,250 | $500 | $500 | $5,000 |

| Workforce Development | $500 | $250 | $125 | $125 | $1,000 |

| Social Determinants of Health | $250 | $500 | $375 | $375 | $1,500 |

| Interim Access Assurance Fund | $500 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $500 |

| Total | $4,000 | $2,000 | $1,000 | $1,000 | $8,000 |

As with the first iteration of the DSRIP, this amendment will be supported with reinvestment of 1115 waiver savings garnered from other 1115 MRT Waiver initiatives. DSRIP will continue to be tracked outside of Medicaid Eligibility Groups (MEGs) as a "Spend Only" demonstration. For this reason, this amendment will not generate any additional waiver savings, nor will it have an impact on waiver enrollment.

Section IX. Summary

DSRIP in NYS is succeeding. The PPS and local partners have built proven approaches to meaningfully reducing avoidable hospitalization. The State, providers, and MCOs have also made great strides toward value–based payment and are well on the way to meeting the VBP Roadmap goals. New York has been an innovator in requiring more advanced VBP contracts to address social determinants and has made great strides resulting in over 70 distinct contracts for SDH interventions thus far.

In order to sustain this success and move transformation forward to a higher level, NY seeks to continue its partnership with the federal government through an amendment to the DSRIP waiver. Expanding DSRIP promising practices will further drive up quality while lowering cost to the State and our federal partners.

Appendix A

Table 1 – New York State DSRIP Program Amendment/Extension Request

| CMS Priorities | DSRIP Promising Practice alignment/Program Extension Areas |

|---|---|

| SUD and the Opioid Crisis | Transforming and Integrating Behavioral Health |

|

Integration and expansion of Medication–Assisted Treatment in primary care and ED settings |

|

|

|

Partnerships with the justice system and other cross–sector collaborations |

|

|

| SMI/SED Demonstration | Transforming and Integrating Behavioral Health |

|

Primary care and behavioral health integration |

|

|

|

Care coordination, care management, and care transitions |

|

|

|

Expansion of Mobile Crisis Teams (MCT) and crisis respite services |

|

|

|

Extend successful practices above in cross–sector collaboration, care transitions, and care management to patients transitioning from IMDs to the community. |

|

|

|

Extend successful practices above in cross–sector collaboration, care transitions and care management to apply to SED children. |

|

|

| Social Determinants of Health | Social Needs, Community Partnerships |

|

Addressing Social Determinants of Health through Community Partnerships |

|

|

| Primary Care Initiatives | Primary Care and Alternative Payment Models |

| CPC+ and Primary Care First VBP 2 | Transforming Primary Care and Supporting Alternative Payment Model |

|

|

| ADDITIONAL PRIORITIES | Children |

| InCK Model through CMMI | Investing in Community Health Workers (CHW) for Chronic Disease Management |

|

|

| Crisis Stabilization: Preventing Unnecessary Behavioral Health Hospitalizations | |

|

|

| Fostering Cross–Sector Collaborations to Target Behavioral Health in Schools | |

|

|

| Long–term Care | Disabled Members and Older Adults |

| Medicare Post–Acute Care Transformation Act of 2014 (the IMPACT Act) 3 | Building Quality Improvement Capacity Across the Care Continuum |

|

|

| Tracking High Utilizers Across Multiple Settings to Bridge Gaps in Coordination | |

|

Appendix B

The PPS examples below elaborate on some of the promising practices outlined in the preceding table and more detailed representations can be found in the UHF Report, "DSRIP Promising Practices: Strategies for Meaningful Change in New York Medicaid". The strategies described suggest opportunities for larger outcome improvement if given the time and resources for effective scaling and replication. There are many examples of similar PPS efforts and these are not intended to represent the full breadth and depth of promising practices that DSRIP has fostered across the State.

Addressing the Opioid Crisis Through the Integration and Expansion of Medication– Assisted Treatment in Primary Care and Emergency Department Settings

- Leatherstocking PPS championed the recruitment, training, and certifying of additional primary care practitioners to provide medication–assisted treatment, thereby improving access to treatment for opioid use disorder.

- Central NY Care Collaborative PPS and SUNY Upstate emergency department providers initiated opioid use disorder treatment for patients, providing transition support through interim services and peer outreach until the patients are able to receive ongoing treatment.

Addressing the Opioid Crisis and Behavioral Health Needs through Partnerships with Education, Law Enforcement/Justice System and Other Cross–Sector Collaborations

- Adirondack Health Institute PPS focused on diversion programs where treatment for SUD and behavioral health issues are alternatives to arrest and incarceration. Law enforcement officials were trained in crisis intervention strategies and resources. Care managers meet with people with behavioral health issues in the jail to develop plans for connecting these individuals with post–release community services. Pre– and post–arraignment diversion programs focus on supporting treatment and recovery for behavioral health needs, such as opioid use disorder.

- 100 Schools Project is a collaboration to strengthen the capacity of schools in underserved communities to meet their students´ disproportionately greater behavioral health needs. Four PPSsâBronx Health Access, Bronx Partners for Healthy Communities, Community Care of Brooklyn, and OneCity Healthâand the Jewish Board of Family and Children´s Services partnered with four behavioral health providers, New York City (NYC) government units, and underserved NYC public schools. The program focuses on prevention and early identification of behavioral health problems among students, using coaches to train teachers and staff and deliver crisis support and make behavioral health referrals to students and families. In turn, the program also aims to improve students´ educational outcomes, such as reductions in truancy and suspensions. In 2018, about half (49%) of all behavioral health crises where police responded to 911 calls at participating schools were mitigated without an arrest and without the student needing to leave school, compared to a quarter (26%) of such crises across all city schools.

Hot–Spotting High–Risk Behavioral Health Members and Mobilizing Care Teams for Engagement

- Mt. Sinai and Staten Island PPS, in partnership with Health Home and community care management providers, targeted high–risk BH members using utilization and clinical data from the state, as well as hospital and Qualified Entity sources. The PPSs worked with patients´ providers to enroll them in six–month intensive care management programs linking appropriate outpatient care and community social supports.

Expanding Primary Care within Behavioral Health Sites and Behavioral Health within Primary Care Sites

- Montefiore Hudson Valley PPS and Suffolk Care Collaborative PPS bridged gaps in care management by integrating physical and behavioral health care through the operation of van–based mobile health centers that deliver primary care services and screenings to patients at multiple behavioral health provider sites.

- Refuah Community Health Collaborative PPS integrated behavioral health services into primary care settings through multiple strategies, including: data sharing, workforce expansion, development of shared behavioral health protocols, new workflows and delivery models in primary care settings, and investments in co–location.

Care Coordination, Care Management, and Care Transitions for At–Risk Patients

- The Community Care of Brooklyn PPS created Transitional Care Teams (TCTs) of nurses and care managers to work with patients at risk for 30–day readmission, by addressing medication concerns and providing condition–specific education. Post–intervention reductions in TCT patients with ED visits ranged from 1.5% to 6.9%, and reductions in TCT patients with hospital admissions ranged from 11.5% to 18.7%,

- Community Partners of Western New York PPS fostered community–based telemedicine programs that support effective care transitions and provide ongoing in–home ED triage and monitoring for special subpopulations such as individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities and chronic disease patients with palliative care needs.

- Staten Island PPS developed a comprehensive care coordination program supporting individuals identified as "at risk" of future Health Home eligibility by building partnerships between the PPS, two Health Homes, a community health center, and a CBO to train care coordinators in providing health coaching and community support to the at–risk individuals.

Integration of Peer Support (SUD, HIV, BH) and CHWs for Specific Populations for Improved Outcomes

- Montefiore Hudson Valley Collaborative PPS partnered with an inpatient detoxification and rehabilitation facility to hire two certified peer recovery coaches to meet a variety of needs for individuals transitioning out of the facility into early recovery. During calendar year 2018, peer recovery coaches ensured that 100% of the 122 transitioning patients attended their first outpatient appointment. Of those, 80% of recovering patients attended their first appointment within seven days of discharge and nearly 96% kept their second appointment. Patients completed more routine discharges, experienced better transitions to, and long– term engagement with, outpatient treatment, and had lower rates of readmissions.

- WMCHealth PPS partnered with community BH clinicians and peers to create an inpatient psychiatric transitions program including a meeting with patients in the hospital prior to discharge, an in–home assessment 48 hours post–discharge, and follow–up support with navigating medical appointments and community–based resources.

- New York–Presbyterian PPS, building on its three existing Designated AIDS Centers, the hospital EDs, and ambulatory care network, further transformed its already robust HIV/AIDS care and prevention services with the involvement of six CBOs, Community Health Workers, and peers who were vital to the outreach efforts necessary to make a population–level impact.

CHWs/Peer Mentors for Chronic Disease Management of Asthma and Diabetes

- OneCity Health, the largest PPS, trained 29 CHWs across 8 CBOs to be deployed in the home visitation program for asthma. Clinicians develop Asthma Action Plans (AAPs) for children with asthma and CHWs visit the families´ homes, supporting the AAPs and arranging remediation when asthma triggers are identified. Within a six–month period, OneCity reports the pediatric asthma admission rates (PDI–14) decreased by 25%.

- WMCHealth PPS implemented evidence–based self–management programs for diabetes in partnership with CBOs and peer mentors. The PPS partnered with CBOs to implement the Stanford University Self–Management Resource Center model, while also initiating a one– on–one peer mentoring pilot for Medicaid patients with uncontrolled diabetes.

Expansion of Mobile Crisis Teams and Crisis Respite Services for Behavioral Health

- Three upstate PPS (Central NY Care Collaborative, Care Compass Network and Better Health for Northeast NY) have expanded the number and capacity of Mobile Crisis Teams in 18 counties, increasing timely access and reducing emergency use for BH needs. Crisis respite capacity has also been built to provide more appropriate settings for BH treatment.

- Nassau Queens PPS partnered with Northwell Health to support opening a Children´s BH urgent care center for children age 5–17, co–located with pediatric ambulatory services. With mental health service access limited, the center serves to bridge gaps in treatment, helping to coordinate care with schools, pediatricians, and other healthcare professionals.

Addressing Social Determinants of Health through Community Partnerships

- Nassau Queens PPS partner Northwell Health implemented a "Food as Health" program to connect food insecure patients who have a nutrition–related diagnosis with a structured network of resources in the community including the delivery of medically tailored meals as appropriate. Results have shown the services may have contributed to lower A1C scores, increased primary care visits, increased SNAP enrollment, and decreased food insecurity, ED use, and readmissions.

- Finger Lakes PPS partnered with CBOs, BH providers, care management agencies, and FQHCs to utilize trained community navigators to build on its patient activation efforts and connect over 17,000 individuals to medical services and social resources. The PPS reports that these efforts have helped decrease potentially preventable ED visits and increase access to primary care.

Transforming Primary Care

- PPS and State Innovation Model (SIM) efforts provided practice transformation support and significantly increased the level of advanced primary care recognition in NYS, enhancing the capacity of these practices to manage complex patients and participate in integrated delivery systems, paving the way towards engaging in population health and VBP arrangements. New York has over 9000 clinicians who are PCMH–recognized.

- SOMOS PPS is among the state´s leaders in supporting small practice providers where 646 of their affiliated clinicians achieved PCMH recognition. SOMOS invested in training and deployment of CHWs to support the practices in care management, outreach and education efforts with their patients.

________________________________________

1. An independent not–for–profit organization working to build a more effective health care system in New York 1

2. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press–releases/hhs–news–hhs–deliver–value–based–transformation–primary–care 2

3. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality–Initiatives–Patient–Assessment–Instruments/Post–Acute–Care–Quality–Initiatives/IMPACT–Act–of–2014/IMPACT–Act–of–2014–Data–Standardization–and–Cross–Setting–Measures.html3

Follow Us