Board for Professional Medical Conduct 2008-2009 Annual Report

- The Board for Professional Medical Conduct 2008-2009 Annual Report is also available as a printable PDF (PDF, 387KB, 31pg.)

Office of Professional Medical Conduct

New York State Department of Health

433 River Street, Suite 1000

Troy, NY 12180-2299

| Main Number: | 518-402-0836 |

| Complaints/Inquiries: | 1-800-663-6114 |

| E-mail Inquiries: | opmc@health.state.ny.us |

| Physician Information: | www.nydoctorprofile.com or www.nyhealth.gov |

- Kendrick A. Sears, M.D., Chair, Board for Professional Medical Conduct

- Michael A. Gonzalez, R.P.A.-C, Vice Chair, 2008, Board for Professional Medical Conduct

- Carmella Torrelli, Vice Chair, 2009, Board for Professional Medical Conduct

- Ansel R. Marks, M.D., J.D., Executive Secretary, 2008, Board for Professional Medical Conduct

- Katherine Hawkins, M.D., J.D., Executive Secretary, 2009, Board for Professional Medical Conduct

- Keith W. Servis, Director, Office of Professional Medical Conduct

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- General Program Information

- Overview of New York's Medical Conduct Process

- Board Activities

- Program Highlights

- Summary Statistics

- Disciplinary Action Vignettes

Executive Summary

The State Board for Professional Medical Conduct (Board) was created by the New York State Legislature in 1976 and, with the Department of Health's (DOH/Department) Office of Professional Medical Conduct (OPMC), administers the State's physician discipline program. Its mission is patient safety -- to protect the public from medical negligence, incompetence and illegal or unethical practice by physicians.

The Board, through the OPMC, investigates complaints made against physicians, physician assistants and specialist assistants and prosecutes those charged with misconduct. It also monitors licensees who have been impaired or who have been placed on probation by the Board.

In 2008, Governor David A. Paterson signed legislation designed to improve patient safety, including enhancing New York's physician discipline program. The Patient Safety Law implemented improvements to ensure transparency of the disciplinary process, increase access to up-to-date information about physicians, better empower the Board and the OPMC to identify potential misconduct and ensure that patients have appropriate access to their medical records. As part of the Department's ongoing patient safety efforts, effective January 14, 2008, physicians are required to report adverse events following office-based surgery (OBS) to the Department. When potential misconduct exists, OPMC investigates.

Additional highlights for 2008 – 2009 include:

- In 2008, according to the Federation of State Medical Boards (www.fsmb.org) the Board took more serious actions than any other state in the nation, including loss of license actions.

- The number of complaints received reached an all-time high in 2009 – 9,103 – a 24 percent increase over the number received five years ago. In spite of the increases, the average time to complete an investigation remains under one year.

- The Physician Monitoring Program (PMP) monitored 1,287 licensees during 2009.

- The OPMC continued its efforts to improve use of medical malpractice information to identify and investigate potential misconduct. The Office's efforts focused on implementing the Patient Safety Law requirements and improving compliance with medical malpractice reporting requirements.

- A new web-based investigation case tracking system, known as iTrak, was developed and implemented in 2008. This enhanced system gives investigators more information at their fingertips and managers better capability to track caseloads, monitor investigative progress and allocate resources where needed.

General Program Information

Board for Professional Medical Conduct

The State Board for Professional Medical Conduct, with the Department of Health's Office of Professional Medical Conduct, administers the State's physician discipline program. Its mission is to protect the public from medical negligence, incompetence and illegal or unethical practice by physicians.1 The Board is a vital patient safety protection for those who access New York's health care system.

Public Health Law (PHL), Section 230(14) states:

- The Board shall prepare an annual report for the legislature, the governor and other executive offices, the medical profession, medical professional societies, consumer agencies and other interested persons.

In 1976, the New York State Legislature established the authority for the physician discipline program within the DOH and created the Board. The Board became responsible for investigating complaints, conducting hearings and recommending disciplinary actions to the State Education Department (SED). The SED and its governing body, the Board of Regents, were responsible for determining final actions in all physician discipline cases.

In 1991, the DOH assumed full disciplinary authority, including the revocation of licenses, for physicians, physician assistants and specialist assistants. The Board was granted sole responsibility for determining final administrative actions in all physician, physician assistant and specialist assistant discipline cases. All other health care professionals (e.g., nurses, dentists, podiatrists, etc.) continue to be licensed and disciplined by the SED.

The Board is comprised of physician and non-physician lay members. Physician members are appointed by the Commissioner of Health with recommendations for membership received largely from medical and professional societies. The Commissioner, with the approval of the Governor, appoints lay members of the Board. By law, the Board of Regents appoints 20 percent of the Board's membership. Currently, the membership is comprised of 100 physicians (representing 24 different medical specialties) and 44 lay members, including five physician assistants.

The Board's roles and responsibilities throughout the disciplinary process are explained in detail in this report. Through its activity, the Board ensures the participation of both the medical community and the public in this important patient safety endeavor.

1In this report, the term "physician" refers to licensed medical doctors [MDs], doctors of osteopathy [DOs], physicians practicing under a limited permit, medical residents, physician assistants and specialist assistants.

Office of Professional Medical Conduct

The OPMC carries out the objectives of the Board. The OPMC's mission is to protect the public through the investigation and, when necessary, the prosecution of professional misconduct involving physicians. The OPMC also monitors physicians when required as a result of a Board action. Through its investigative and monitoring activities, the OPMC strives to deter medical misconduct and promote and preserve the appropriate standards of medical practice.

The OPMC operates a central office in Troy, New York and seven field offices (Troy, Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, New York City, New Rochelle and Central Islip).

The OPMC:

- Investigates all complaints and, with assistance of counsel, prosecutes physicians formally charged with misconduct;

- Monitors physicians whose licenses have been restored following a temporary surrender due to incapacity by drugs, alcohol or mental impairment;

- Monitors physicians placed on probation;

- Oversees the contract with the Medical Society of the State of New York's Committee for Physician Health (CPH) – a non-disciplinary program to identify, refer to treatment and monitor impaired physicians; and

- Supports the activities of the Board, including managing the appointment process, training, assisting with committee work and policy development, recruiting medical experts and coordinating the procedures for more than 100 hearing committees that are convened annually.

Overview of New York's Medical Conduct Process

The Board and the OPMC administer the State's physician discipline program, which is governed by two statutes. The process is defined in Public Health Law Section 230, while the definitions of misconduct are found in Sections 6530 and 6531 of the Education Law.

The process involves the receipt and review of complaints, the investigation of allegations of misconduct and the prosecution of cases in which the evidence supports the presence of misconduct. Throughout the process, specific protocols are followed to ensure thorough, appropriate investigations and accurate findings based on evidence. Just as importantly, the process ensures appropriate due process for the physician under review.

Patient Safety Law of 2008

On August 5, 2008, Governor David A. Paterson signed legislation designed to dramatically improve patient safety, enhance the State's authority in medical investigations and help to prevent future infection control violations. The landmark legislation boosts the physician disciplinary system and increases the authority of the DOH in epidemiological investigations while also giving consumers access to more information about physicians, particularly those charged with misconduct, which is available by accessing the DOH web site, including the Doctor Profile. Most provisions of the law became effective November 3, 2008.

The law enhances the existing system of professional discipline as follows:

- Improves public access to information and ensures transparency of the physician discipline process by requiring the Board to make charges public no earlier than five business days after charges are served upon a physician in certain situations.

- Improves the currency of publicly available information by requiring physicians to more regularly update their physician profiles. The profiles, which contain information such as educational background, practice area and legal actions (which are available to the public at www.nydoctorprofile .com) must now be updated as a condition of re-registration of the doctor's medical license. Information about licensure actions is available through a link to the OPMC web site.

- Enhances patient safety by allowing OPMC, in certain circumstances, to more easily obtain a physician's own personal medical records, if there is reason to believe that he or she may be impaired by alcohol, drugs, physical disability or mental disability or has a medical condition that may be relevant to an inquiry into a report of a communicable disease.

- Strengthens OPMC's ability to proactively identify potential misconduct by requiring the Office to continuously review information about medical malpractice claims and open investigations when potential misconduct is identified.

- Requires physicians who have lost their right to practice medicine to take steps to facilitate appropriate transfer of patient care and to safeguard and make accessible the medical records of both current and former patients.

- Adds a new definition of misconduct for violation Section 230(d) of the Public Health Law relating to the practice of OBS.

- Adds a new definition of misconduct for failure to respond in a timely manner to a DOH or local health department request for information as part of an inquiry into a report of communicable disease.

Complaints

The OPMC is required by New York State Public Health Law Section 230(10) to investigate every complaint it receives. Complaints come from many sources: patients, their families and friends, health care professionals, health care facilities and other individuals or organizations. Complaints may also be opened as a result of a report in the media or a referral from another government agency.

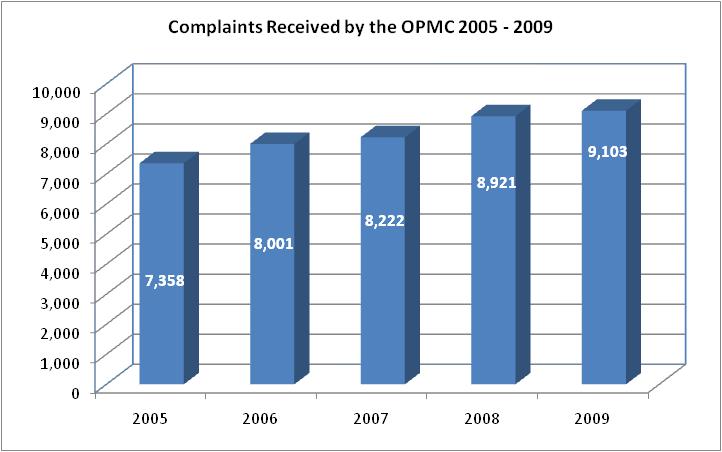

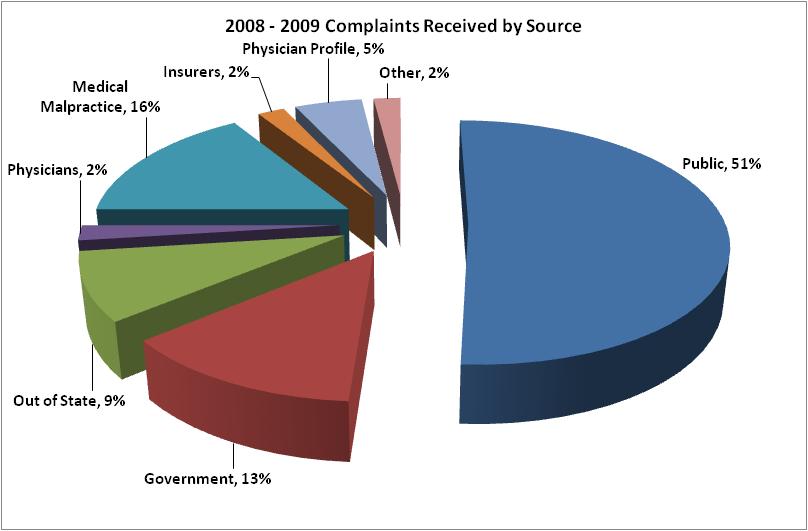

In 2009, the OPMC received 9,103 complaints, compared to 8,921 in 2008. The 2009 volume is 24 percent higher than in 2005, when 7,358 complaints were received (see Figure 1). About 51 percent of the complaints received came from the public (see Figure 2).

Every complaint is reviewed to determine whether the subject of the complaint is a physician (thereby falling under the OPMC's jurisdiction), and whether the allegation, if found true, would be medical misconduct. Many complaints fail to meet one or both of these thresholds, such as when the allegation is a billing dispute or when the complaint is related to a health care professional other than a physician.

In these instances, the case is closed administratively and the physician is not made aware of the complaint. The OPMC makes referrals to other agencies as appropriate.

Figure 1

Source: The Office of Professional Medical Conduct

Figure 2

Source: The Office of Professional Medical Conduct

Investigations

When OPMC commences an investigation, the physician under review is notified either by letter or through a telephone call. A letter requesting patient records is usually an indicator that an investigation is under way. An investigator may call and say there is a complaint and ask for records or to discuss the matter.

The OPMC investigation is a fact-gathering process. Investigators and clinicians, including physicians, review medical records and interview anyone who may have knowledge relevant to the allegation. The goal of this activity is to gather and analyze all relevant information to determine whether the evidence suggests that there was misconduct.

OPMC investigations include strong confidentiality protections. For example, Public Health Law requires the OPMC to keep the name of the complainant confidential. The very existence of an investigation is also confidential until completed. These provisions exist for the protection of both the complainant and the physician being investigated.

The OPMC also ensures that the physician has due process throughout. The physician may be represented by an attorney and may submit information to the OPMC at any time during the investigation. State Public Health Law Section 230(10) requires that a physician be given the opportunity to be interviewed by OPMC staff to provide an explanation of the issues under investigation if the OPMC intends to refer the matter to the Board. This interview may be conducted in person or over the telephone, and the physician may have an attorney present. The physician may bring a stenographer to transcribe the interview, at his/her expense.

In many cases, even if the matter does not result in a referral to the Board, the physician is contacted to respond to the issues in the complaint. Cases are not referred to the Board when there is insufficient evidence to proceed or the issues are determined at that point to be outside of its jurisdiction. Physicians contacted in such cases are advised by letter that the matter is closed.

Part of the fact-gathering process involves the Board. Public Health Law Section 230(7) provides that a committee of the Board may direct a physician to submit to a medical or psychiatric examination when the committee has reason to believe the licensee may be impaired by alcohol, drugs, physical disability or mental disability. These evaluations provide valuable expert information about the possible presence of an impairment.

The Board's authority was expanded through the Patient Safety Law. Section 230(7) now authorizes the Board to direct the OPMC to obtain medical records or other protected health information pertaining to the licensee's physical or mental condition when the Board has reason to believe that the licensee may be impaired by alcohol, drugs, physical disability or mental disability or when the licensee's medical condition may be relevant to an inquiry into a report of a communicable disease. In addition, the Board can now direct a physician to submit to a clinical competency examination. The Board's expanded authority provides greater protections for the public, empowering the Board to determine the presence and magnitude of any issues facing the physician.

A critical component of the investigation process is the expert review. Public Health Law Section 230(10)(a)(ii) requires that medical experts be consulted when an investigation involves issues of clinical practice. Physicians who are board-certified in their specialty, currently in practice and who are not employed by the OPMC, review the investigative information and identify whether the physician under review met minimum standards of practice or did not. The peer review aspect of the process is key to making fair and appropriate determinations.

When the investigation finds evidence that appears to indicate that misconduct has occurred, the evidence is presented to an investigation committee of the Board for review. The investigation committee is comprised of two physician Board members and one public member. If a majority of the committee concurs with the Director of the OPMC (Director) that sufficient evidence exists to support misconduct, and after consultation with the Executive Secretary to the Board, the Director directs counsel to prepare charges.

The Patient Safety Law of 2008 requires the Board to make charges public no earlier than five business days after charges are served upon a physician when the investigation committee has unanimously voted that the evidence supports misconduct and a hearing is warranted. In cases where the investigation committee votes to proceed with a hearing, but the vote is not unanimous, they will vote to decide whether or not such charges should be made public. A statement advising that the charges or determinations are subject to challenge by the physician will accompany the charges.

The investigation committee may take actions other than concurring that a disciplinary hearing is warranted. The committee may recommend to the Commissioner of Health that a physician's practice be summarily suspended because he or she poses an imminent danger to the public health. If there is substantial evidence of professional misconduct of a minor or technical nature or of substandard medical practice which does not constitute professional misconduct, the Director, with the concurrence of the investigation committee, may issue an administrative warning and/or provide for consultation with a panel of one or more experts, chosen by the Director. Administrative warnings and consultations are confidential.

Disciplinary Hearings

In some cases that are referred for charges, a disciplinary hearing is avoided through a consent agreement signed by the physician, the Director and the Board Chair. Such agreements put terms in place that adequately protect the public and address the misconduct identified by the investigation without incurring the time and costs of a hearing. Many cases, however, proceed to a disciplinary hearing.

If the case proceeds to a hearing or the Commissioner of Health orders a summary suspension, another three-member panel, including two physicians and one lay member, is drawn from the Board to hear the case. A hearing is much like a trial, with the Board panel serving as the jury. An administrative law judge is present to assist the committee on legal issues. A DOH attorney presents the State's case, and physicians generally choose to be represented by counsel. At the hearing, evidence is presented and testimony may be given by witnesses for both sides.

Public Health Law requires that hearings start within 60 days of the service of charges or, in cases of summary suspension, within ten days of the service of charges. The last hearing day must be held within 120 days of the first hearing day. The hearing committee's decision must be issued within 60 days of the last hearing day. Changes in these time frames can be made by agreement of both sides.

A hearing committee first rules on whether misconduct exists or not, deciding whether to dismiss or sustain some or all of the charges against the physician. If the hearing committee sustains charges, it decides on an appropriate penalty. Penalties can range

from a censure and reprimand to license revocation. The committee may also suspend or annul a physician's license, limit his or her practice, require supervision or monitoring of a practice, order retraining, levy a fine or require public service. Hearing committee determinations are immediately made public.

Revocations, actual suspensions and license annulments go into effect at once and are not stayed (delayed) if there is an appeal to the Administrative Review Board. Other penalties are stayed until the period for requesting an appeal has passed, and if there is an appeal, disciplinary action is stayed until there is a resolution.

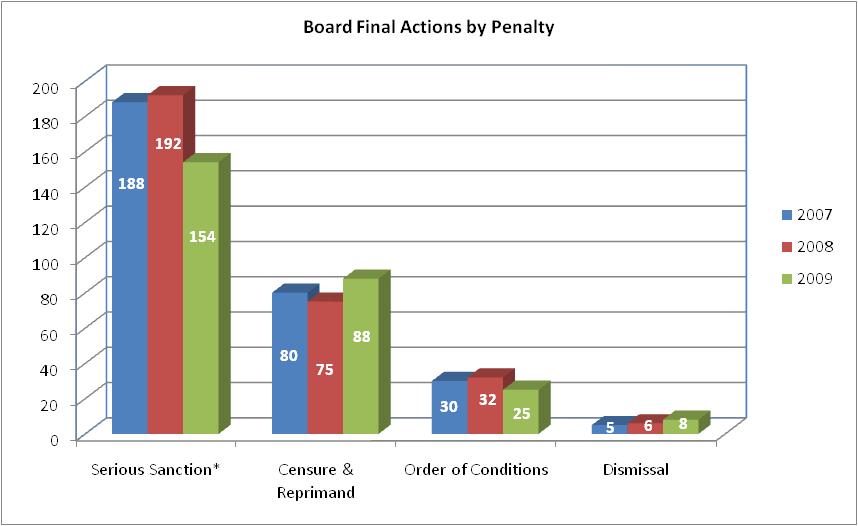

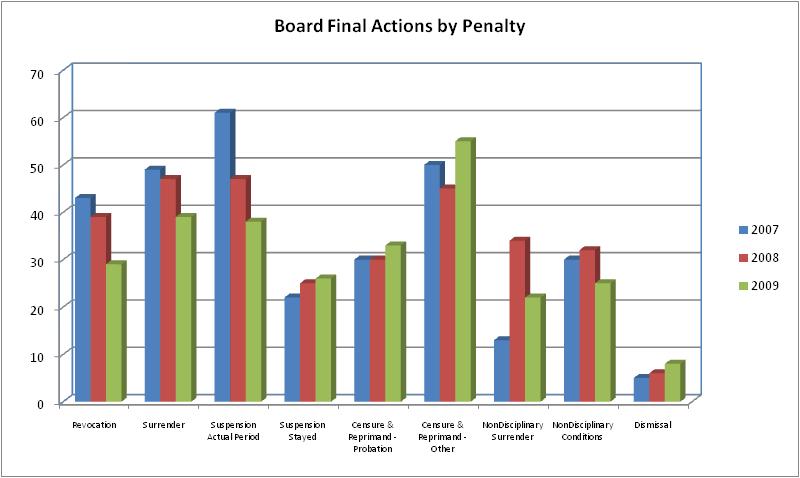

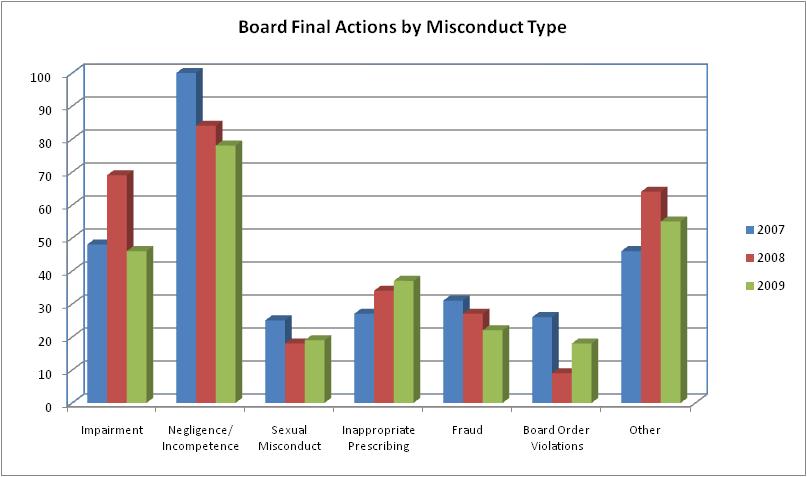

In 2008, the Board issued 305 final actions and in 2009, the Board issued 275 final actions, most of which were serious sanctions (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

* Serious sanctions include revocations, surrenders and suspensions of medical licenses.

Source: The Office of Professional Medical Conduct

Appeals

Either side may appeal the decision of a hearing committee to the Administrative Review Board (ARB). The ARB is a standing panel, comprised of three physician Board members and two lay Board members. The ARB hears all administrative appeals.

Notices of appeal to the ARB must be filed within 14 days of the service of a hearing committee decision. Both parties have 30 days from the service of the notice of appeal to file briefs and another seven days to file a response to the briefs. There are no appearances or testimony in the appeals process.

The ARB reviews whether the determination and penalty of the hearing committee are consistent with the hearing committee's findings and whether the penalty is appropriate. The ARB must issue a written determination within 45 days after the submission of briefs.

In 2008 and 2009, the ARB issued 41 decisions. Of those, 38 decisions upheld the hearing committee determination, and in 24 decisions, the ARB upheld the penalty imposed by the original hearing committee. In the 17 cases in which the penalty was modified, the ARB increased the penalty 15 times and decreased the penalty twice. The experience in both years is consistent with that in 2007.

Figure 4

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative Review Board Decisions | 13 | 22 | 19 |

| Hearing Committee Determinations Upheld | 12 | 21 | 17 |

| Hearing Committee Determinations Not Upheld | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Hearing Committee Penalties Upheld | 8 | 13 | 11 |

| Hearing Committee Penalties Increased | 4 | 7 | 8 |

| Hearing Committee Penalties Decreased | 1 | 2 | 0 |

Source: The Office of Professional Medical Conduct

Physician Monitoring Program

Impaired Physicians

Public Health Law Section 230(13) allows a physician who is temporarily incapacitated, is not able to practice medicine and whose incapacity has not resulted in harm to a patient, to voluntarily surrender his or her license to the Board. The OPMC carries out this provision to identify these impaired physicians, rapidly remove them from practice, refer them to rehabilitation and place them under constant monitoring upon their return to active practice to ensure that they practice safely.

Upon receipt of a report that a physician may be impaired, OPMC immediately conducts an investigation to determine the facts. If the evidence indicates that there is a problem with alcohol, drugs, mental illness or physical disability, OPMC may seek a non-disciplinary temporary or permanent surrender of the physician's license. The Board may accept and hold such licenses during the period of incapacity.

When a surrender is accepted, the Board promptly notifies entities, including the SED and each hospital at which the physician has privileges. The physician whose license is surrendered notifies all patients of temporary withdrawal from the practice of medicine. The physician is not authorized to practice medicine, although the temporary surrender is not deemed to be an admission of permanent disability or misconduct. At the end of 2009, the OPMC was holding 79 temporarily surrendered licenses.

A surrendered license may be restored when the physician can demonstrate to the Board that he/she is no longer incapacitated for the active practice of medicine. A Board committee (twophysicians and one lay member) convenes a restoration proceeding to determine whether the physician has made an adequate showing as to his or her rehabilitation.

Three physicians petitioned the Board for restoration in 2008, one of whom was granted restoration. In 2009, two physicians petitioned the Board for restoration of a temporarily surrendered licenses, both of whom were restored.

If the Board restores the license, the physician is placed under a minimum monitoring period of five years. Monitoring terms generally require abstinence from drugs and/or alcohol with random and unannounced drug screens, a medical practice supervisor, a treatment monitor and self-help group attendance such as Alcoholics Anonymous. As of December 31, 2009, the OPMC was monitoring 393 licensees who were in recovery from alcohol, drugs, mental illness or physical disability.

Probation

The OPMC is also responsible for monitoring physicians placed on probation, pursuant to a determination of professional misconduct, under PHL Section 230(18). The Board places a physician on probation when it determines that he/she can be rehabilitated or retrained in acceptable medical practice. It is the same underlying concept used in placing physicians impaired by drugs/alcohol under monitoring.

The law authorizes the OPMC to perform appropriate monitoring activities, including but not limited to, reviewing a random sample of the licensee's office records, patient records and hospital charts, conducting onsite visits, assigning another physician to monitor the licensee's practice, auditing billing records, testing for the presence of alcohol or drugs and requiring that the licensee work in a supervised setting.

Additionally, each physician on probation meets with the OPMC monitoring investigator and the medical director to review the terms and conditions of his/her Board order and discuss patient care or other issues identified during probation.

The prime focus of probation, in addition to monitoring compliance, is education and remediation. Working with professional societies, hospitals and individual practitioners, the probation program allows for close scrutiny of the physician's practice, early identification of necessary adjustments to the probation terms and support for the physician's rehabilitation and training. During 2009, the OPMC monitored 1,287 licensees. The OPMC pursues physicians who violate terms of probation. In 2009, the Board referred 16 physicians to a disciplinary hearing for failure to comply with probation terms. In 2008, the Board referred 31 physicians and in 2007, 22 physicians were referred for prosecution based on this issue.

Board Activities

The Board welcomed a new Vice Chair and Executive Secretary in 2009, to carry on the outstanding work of their predecessors.

Vice Chair

On July 9, 2009, Carmela Torrelli was appointed the Board's new Vice Chair. Ms. Torrelli joined the Board as a lay member on November 1, 1998.

A graduate of Adelphi University with a degree in Business Administration, she currently works as a Commissioned Bank Examiner/Fraud Specialist with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) in New York City.

In that role, she analyzes the safety and soundness of financial institutions of varying size, structure and complexity, including institutions subject to regulatory actions. Ms. Torrelli also reviews the private banking departments and international operations of financial institutions and conducts special investigations relating to insider trading, money laundering and bank fraud. Ms. Torrelli has served on the Board's Fraud Advisory Committee since 2007 has served on the Federation of State Medical Boards' Finance Committee.

Ms. Torelli replaces Michael A. Gonzalez, R.P.A.-C. Mr. Gonzalez was appointed to the Board in March 1989 and served as Vice Chair from 2002 - 2009. Mr. Gonzalez served effectively as Board Vice Chair and as member of several Board committees. His knowledge as a practicing Physician Assistant and his counsel to the Chair in developing and implementing Board policy have been valuable to maintaining the effectiveness of the Board. The Board thanks Mr. Gonzales for his outstanding contributions.

Executive Secretary

In January 2009, Kendrick A. Sears, M.D., Chair of the Board, appointed Katherine A. Hawkins, M.D., J.D., as Executive Secretary of the Board.

Dr. Hawkins is a graduate of Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons and is board certified in Internal Medicine with a specialty in hematology. Before she joined OPMC, Dr. Hawkins spent nearly 30 years in administration, teaching and clinical practice in New York City at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, St. Luke's Roosevelt Hospital, Beth Israel Medical Center and Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Dr. Hawkins is also a graduate of Fordham University Law School and admitted to the New York State Bar. Since 2002 she has practiced law, concentrating on medical malpractice, while continuing a small medical practice. She has served on a number of medical and legal committees and has a special interest in professional standards.

She succeeds Ansel Marks, M.D., J.D., who stepped down after nearly 12 years as Executive Secretary. Dr. Marks continues nearly 30 years of outstanding service to the Board and the program, including eight years as a Board member and as a Medical Coordinator for the OPMC.

Committee for Physician Health and Board for Professional Medical Conduct

The OPMC is responsible for overseeing the contract with the Medical Society of the State of New York, Committee for Physician Health (CPH) – a non-disciplinary program to identify, refer to treatment and monitor impaired physicians. The CPH and the Board established a Joint Committee to monitor current activities and develop recommendations that will enhance New York's impaired physician programs to both protect the public and assist physicians in need.

The Joint Committee commenced a review of the decision of the Medical Board of California on July 1, 2008, to end its diversion program for the monitoring of impaired physicians following a state auditor's criticisms of the program. The review compared New York's impaired physician programs with the California auditor's cited deficiencies. The Joint Committee recognized many areas of program strength including, in particular, the quick response to cases of suspected relapse. The Joint Committee also identified recommendations for technology improvements to efficiently acquire data for both clinical and administrative program oversight, new formal written agreements with CPH work site monitors and updates to the CPH policies and procedures.

Hospital Reporting Requirements

Hospitals are statutorily required to report any information to the Board that reasonably appears to show that a licensee may be guilty of misconduct. In 2009, OPMC received 122 reports from hospitals regarding physician misconduct, 16 (13 percent) of which were related to concerns of physician impairment. These figures are consistent with the OPMC's 2007 and 2008 experience. In 2007, 123 hospital reports were received, 22 (18 percent) of which involved impairment and in 2008, 99 reports were submitted including 13 (13 percent) related to impairment.

Program Highlights

Complaints and Investigations

- During 2005-2009, the number of complaints received has increased an average of six percent per year. In 2009, there was a 24 percent increase in complaints received (9,103) compared to the number of complaints (7,358) received during 2005.

- The number of investigations initiated has increased over the last five years. In 2009, 4,127 investigations were initiated, which was a 28 percent increase over the 3,231 initiated in 2005. In spite of the increase, the average time to complete an investigation remains under one year (264 days in 2008 and 285 days in 2009).

- In 2008, the Board took 305 final actions of which 167 included loss of license or period of suspension. In 2009, the Board took 275 final actions of which 128 included loss of license or period of suspension.

Improving the Use of Medical Malpractice Information to Identify Potential Misconduct

With a growing national interest in and concern about the possibility of medical malpractice experience as a predictor of misconduct, the OPMC continued its efforts to identify how to best use malpractice information to identify and investigate potential medical misconduct.

State Insurance Law, Chapter 28, Article 3, Section 315, mandates the reporting of any claim filed for medical malpractice against a physician, physician assistant or specialist assistant, to be reported to the Commissioner of Health, as well as the Superintendent of Insurance.

The Patient Safety Law of 2008 directs the OPMC to continuously review medical malpractice information for the purpose of identifying potential misconduct.

The OPMC's efforts in 2008 - 2009 focused on two areas:

- Implementing the Patient Safety Law requirements the OPMC to work with the Department's Patient Safety Center to identify potential criteria for establishing a misconduct investigation based on a review of medical malpractice information. The OPMC reviewed potential criteria such as claim volume and frequency, payout volume and frequency, payout source (settlement vs. judgment) and payout dollar amount. The OPMC adopted payout frequency as one criterion upon which to open a misconduct investigation. Specifically, if a physician pays six or more claims over the past five years, the OPMC opens a misconduct investigation.

In addition, the OPMC continues its review of its current criteria – dollar amount of individual case award (specific by specialty), outcome of death and any judgment award – used to open a misconduct investigation. This review will continue with an expectation that criteria for opening a misconduct investigation will be modified in 2010.

The OPMC is also considering other sources of information to better identify licensees who, based on their malpractice experience, warrant OPMC review.

- Improving compliance with medical malpractice reporting requirements. The OPMC and the State Insurance Department (SID) are working together to improve compliance with reporting requirements. This work will continue in 2010 through collaboration with New York State medical malpractice insurers, hospitals and other mandated reporters to improve the utility of the Medical Malpractice Data Collection System (MMDCS) and identify other improvements to ensure complete and accurate reporting.

Ensuring Safety in Office-based Surgery Settings

As of January 14, 2008, licensees were required to report adverse events following OBS to the Department's Patient Safety Center (PSC). Adverse events that must be reported include: 1) patient death within 30 days; 2) unplanned transfer to the hospital; 3) unscheduled hospital admission within 72 hours of the OBS for longer than 24 hours; or, 4) any other serious or life-threatening event. Failure to report an OBS adverse event within one business day of when the licensee became aware of the adverse event may constitute professional misconduct. During 2008, ten cases of OBS adverse events were referred to OPMC for investigation of possible negligent care and treatment. In 2009, 24 cases were referred.

Additional provisions of the law, effective July 14, 2009, require physicians to perform OBS only in accredited practice settings. The OPMC will continue to provide education and oversight as these new requirements are enacted.

Improving Case Management

The OPMC continually develops tools to assist managers and investigators monitor the ever-growing volume of complaints received and investigations initiated. The Office implemented a statewide automated case tracking system in December 2007. The system includes important information about complaints and investigations that allows managers to track the progress of investigations, ensuring the completion of thorough, comprehensive, accurate investigations as quickly as possible. In 2008, the Office took important steps to improve the quality of the system and its usefulness to program staff.

By transferring the system – called iTrak – to a web-based environment and adding modules that incorporate more information than before, the OPMC has implemented a statewide case tracking system that is easier to use and is more robust. This enhanced system gives investigators more information at their fingertips and managers more capability to track overall caseload and allocate resources where needed.

Internet Access to Physician Information

Information regarding the OPMC and Board can be accessed through the DOH's Web site, www.nyhealth.gov , then clicking on "Physician Discipline." All disciplinary actions taken since 1990 are posted on the OPMC's site, as well as information on how to file a complaint, brochures regarding medical misconduct, frequently asked questions and relevant statutes. In 2009, there were more than 825,000 visits to the OPMC content on the Department's Web site.

Expanding Outreach

During 2008 – 2009, the OPMC Director, Deputy Director and Chair of the Board met with county medical societies and State specialty societies across the state to educate physicians on the changes in the physician discipline process as a result of the Patient Safety Law. These teaching opportunities also provided a forum to renew the OPMC requests for greater physician involvement in the process through the medical expert program. Future outreach efforts are planned for the public, patient groups and practitioners.

New York's Performance in a National Context

The Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) is a national not-for-profit organization representing 70 medical boards within the United States and its territories. The FSMB co-sponsors the United States Medical Licensing Examination with the National Board of Medical Examiners.

The FSMB releases an annual report on medical board performance for all 50 states. In 2008:

- The Board for Professional Medical Conduct took more serious actions (293) than any state in the nation. California was second (275) and Ohio third (160). Serious actions are those that result in restriction or loss of license.

- New York took more actions resulting in the loss of license (215) than any other state in the nation.

- New York's ratio of serious actions per 1,000 physicians increased from 3.42 with a ranking of 11th highest nationwide to 3.59 with a ranking of 9th highest in the nation.

Following release of the FSMB's annual report, Public Citizen, a national consumer advocacy group, issued its annual ranking of state medical board performance. The rankings are achieved using physician population data from the American Medical Association and disciplinary data from the FSMB. For the period 2006-2008, New York ranked 19th in the nation in the number of serious disciplinary actions taken, with 3.73 actions per 1,000 physicians. Alaska ranked first with 6.54 actions per 1,000 physicians and Minnesota was ranked lowest with 0.95 actions per 1,000 physicians. New York ranked 20th in 2002 and 49th in 1991.

While these data provide some context for the program's experience, they should not be the sole basis for evaluating performance. Definitions of misconduct and disciplinary processes and rules vary significantly across states. Without a mechanism to account for these differences, meaningful comparisons are difficult.

Office of Professional Medical Conduct

| Year | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complaints Received | 8222 | 8921 | 9103 |

| Investigations Completed | 8024 | 8568 | 9490 |

| Licensees Referred for Charges | 311 | 339 | 229 |

| Administrative Warnings/Consultations | 99 | 157 | 113 |

| Summary Suspensions* | 16 | 24 | 8 |

| Surrender | 49 | 47 | 39 |

| Revocation | 43 | 39 | 29 |

| Suspension | 83 | 72 | 64 |

| Censure and Reprimand/Probation | 30 | 30 | 33 |

| Censure and Reprimand/Other | 50 | 45 | 55 |

| Dismiss | 5 | 6 | 8 |

| Surrenders under 230(13) | 13 | 34 | 22 |

| Monitoring Agreements | 30 | 32 | 25 |

| TOTAL ACTIONS | 303 | 305 | 275 |

*In 1996, Public Health Law 230 was amended to permit a summary suspension when a licensee has pleaded or been found guilty or convicted of committing an act constituting a felony under New York State Law or federal law, or the law of another jurisdiction which, if committed within this State, would have constituted a felony under New York State Law, or when the duly authorized professional agency of another jurisdiction has made a finding substantially equivalent to a finding that the practice of medicine by the licensee in that jurisdiction constitutes an imminent danger to the health of its people.

Source: The Office of Professional Medical Conduct

Source: The Office of Professional Medical Conduct

Disciplinary Action Vignettes

The following vignettes illustrate the circumstances leading to actual case investigations by the OPMC as well as the subsequent disciplinary actions imposed by the Board.

Case #1 – Dr. A

Dr. A, a Board certified anesthesiologist, was charged with practicing with gross negligence and gross incompetence, negligence and incompetence on more than one occasion, practicing fraudulently, performing unauthorized services and failing to maintain adequate records in connection with the treatment of two patients.

One patient, a 62-year-old male undergoing elective surgical correction of a tibial tendon deficiency, died in the operating room after induction of anesthesia but prior to the commencement of surgery. Dr. A failed to ensure that the equipment to monitor the patient, a capnograph, was operable and failed to monitor the patient's breathing after administering anesthesia. The physician also failed to detect and correct the improper placement of a breathing tube and intentionally recorded a carbon dioxide reading in the patient's chart knowing that the capnograph was not properly functioning and could not give a valid reading.

The second patient case involved similar failures to assure that a capnograph was working properly, failure to cancel the surgery and failure to document the nonfunctional capnograph and the oxygen readings in the patient record.

Pursuant to a Consent Agreement, the physician's license was suspended for six months and the physician was placed on probation for an additional 18 months.

Under the terms of probation, the physician was ordered to undergo a clinical competency evaluation and agree to any remediation recommended. Dr. A's practice was limited to a hospital setting with a practice monitor approved by the OPMC.

Case #2 – Dr. B

Dr. B, a Board certified plastic surgeon who practiced in New York City, entered into a Consent Agreement with the Board, based on a charge of negligence on more than one occasion in his care and treatment of four patients who underwent liposuction in his office.

One patient was hospitalized for multiple perforations of her small intestine. Dr. B was also charged with infusing an inappropriate amount of tumescent solution during the procedures.

In the Consent Agreement, Dr. B agreed to limit his practice to a facility licensed by Article 28 of the New York Public Health Law and to perform only minor procedures in his office. Dr. B also agreed to a period of probation with terms to include practice only when supervised and monitored by physicians in appropriate specialties and approved by the OPMC.

After entering into the Consent Agreement, Dr. B notified the OPMC that he had withdrawn from the practice of medicine, thereby suspending imposition of the probation terms until he resumed medical practice. However, the OPMC learned from a prospective patient that Dr. B was, in fact, practicing medicine and scheduled to perform breast augmentation and tummy tuck procedures, absent the required supervisor and monitor, in a private office setting, in direct violation of his Consent Agreement.

OPMC investigators, prior to the scheduled surgery, conducted an unannounced site visit. The investigators questioned Dr. B regarding his continued practice of medicine in violation of his Board order. The investigators also documented the state of the office where Dr. B planned to perform surgery. The site lacked appropriate emergency resuscitation and/or monitoring equipment and the emergency drug kit contained expired medications. There was an uninspected autoclave and the general condition of the office was dusty and cluttered.

Dr. B surrendered his license to practice medicine.

Case #3 – Dr. C

Dr. C is a plastic surgeon, not board certified, with a solo office-based practice in New York City. Dr. C was charged with 44 specifications of misconduct regarding ten patients. A hearing committee of the Board sustained charges including negligence on more than one occasion, gross negligence, fraudulent practice and failure to maintain medical records.

The hearing committee reported that:

Dr. C displayed a consistent, long-term pattern of negligence, fraud and reckless disregard of the necessity to keep accurate records.

The complete lack of adequate and consistent documentation regarding history, physical examination and operative reports demonstrates a significant departure from acceptable minimum standards of medical practice.

Dr. C's failure to adequately document the care and treatment he provided to each of the patients also constituted negligence since such failure adversely affects patient treatment.

Dr. C wrote operative reports for allegedly medically necessary surgery in every instance where his patients had private medical insurance coverage through a major insurer. However, in each instance, Dr. C failed to inform the insurer that cosmetic surgery was being performed.

Dr. C's medical license was revoked.

On appeal to the Administrative Review Board (ARB), the hearing committee's determination to revoke Dr. C's license was upheld. In addition, the ARB sustained charges of moral unfitness and imposed a fine of $40,000 against Dr. C because he used his medical license fraudulently to obtain unjust enrichment.

The Appellate Division of the New York State Supreme Court upheld the Board's revocation of Dr. C's license.

Case #4 – Dr. D

Dr. D, a medical resident, was charged with being a habitual user of opiates or having a psychiatric condition that impairs the ability to practice, practicing while impaired and fraudulent practice.

Dr. D reported for duty in the operating room while impaired by Oxycodone. Dr. D also, with intent to mislead, forged other physicians' signatures on multiple prescriptions for his own use.

This physician entered into a Consent Agreement in which he agreed that his license would be suspended for an indefinite period of time, but no less than 12 months, after which he may petition the Board for a Modification Agreement staying the indefinite suspension.

Dr. D has not petitioned for modification of the Board order.

Case #5 – Dr. E

Dr. E, a psychiatrist, was charged with allegations of physical contact of a sexual nature between a psychiatrist and patient, gross negligence, negligence on more than one occasion, moral unfitness and failing to maintain accurate records. The charges related to Dr. E's medical care and treatment of two patients, a husband and wife.

A hearing committee of the Board determined that Dr. E engaged in an inappropriate sexual and social relationship with Patient A over a period of many years. The Board noted that despite the patient's attempts to end the relationship, Dr. E exploited her feelings and vulnerabilities for his own gratification. In addition, Dr. E's actions not only put Patient A's well being at risk, but also that of her husband, Patient B. Because Dr. E was treating them both, he exploited the difficulties in their relationship for his own benefit.

In its Determination and Order, the hearing committee noted that it was clear Dr. E's lack of necessary documentation, his concurrent treatment of husband and wife and longstanding sexual relationship with Patient A were serious issues that showed he could not be entrusted with the care of society's most troubled and vulnerable members. Following six days of hearing, the committee revoked Dr. E's medical license.

Dr. E filed an appeal of the decision to the Administrative Review Board, which upheld the revocation imposed by the hearing committee.

Case #6: Dr. F

Dr. F, a board certified OB/GYN, faced charges of fraudulent practice and negligence on more than one occasion involving prescribing via the Internet.

The allegations include that Dr. F knowingly and unlawfully distributed and dispensed Schedule III and Schedule IV controlled substances outside the usual course of medical practice. Controlled substances were ordered by Internet pharmacy customers who logged onto one or more websites sponsored by the pharmacy. The Internet pharmacy customers selected and then prepaid for Schedule III and Schedule IV controlled substances on-line using credit or debit cards.

Dr. F reviewed approximately 50-60 questionnaires each day on the pharmacy's behalf. During his four-month employment with the pharmacy, Dr. F authorized more than 7,000 prescriptions. From these prescriptions, nearly 400,000 dosage units of Schedule III controlled substances were dispensed and nearly 39,000 dosage units of Schedule IV controlled substances were dispensed. The majority of these prescriptions were for hydrocodone.

Dr. F surrendered his license to practice medicine.

State of New York

Department of Health

Richard F. Daines, M.D., Commissioner